R

E

V N

E

X

T

The camera is, undoubtedly, a travel essential in our current age of visual documentation. Whether it is with a professional device or the trusty iPhone and requisite selfie stick, collecting tangible evidence of a place and experience is often on a traveler’s must-do list. If you have ever hesitated on putting your finger on the shutter, then Warhol in China (Hatje Cantz, 2013) will serve as encouragement to capture all the fleeting moments.

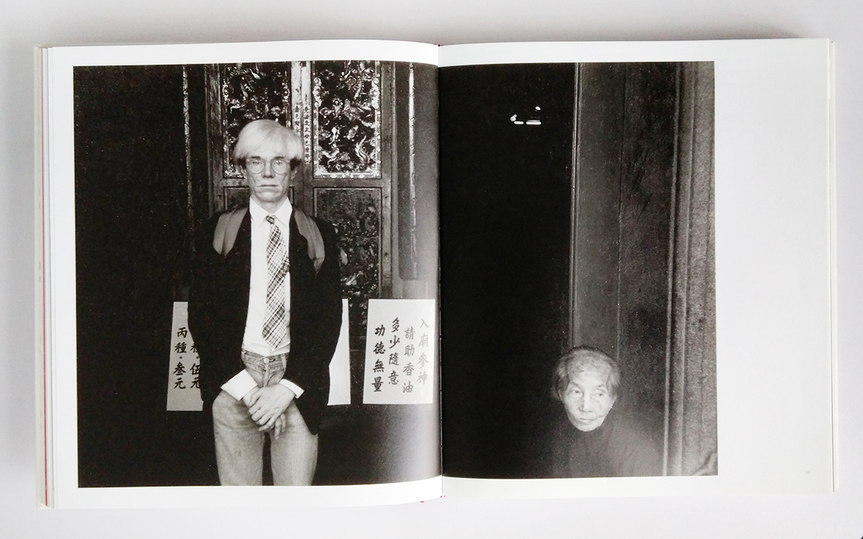

The editors of Warhol in China have compiled a travel chronicle, gathering the legendary Pop artist’s compelling photographs and drawings from his brief trips to Beijing and Hong Kong in 1982, just five years before his death at age 58. Although Warhol’s 35-mm-format photographs from his tour of China have been celebrated individually in publication or exhibition, they have never been done so all together. Accompanying the images are supportive and contextualizing critical essays and interviews—by such prominent art-world figures as author and art critic Tony Godfrey, art collector and advisor Michael Frahm and curator Nicholas Chambers—as well as Warhol’s own diary entries that were logged during the visit to China. Although these accounts were meant as a practical tool for recording his travel expenses at the time, they now provide insight into the artist’s mindset during the trip. An insightful foreword by Ai Weiwei grounds the book, foreshadowing the looming impact Warhol had on Ai and other revolutionary Chinese contemporary artists. What emerges in the book is a skillfully-curated and sensitively-sequenced collection of visual testaments which, like all of Warhol’s works, erase the traditional distinctions between fine art and popular culture.

Warhol’s earliest artistic association with China was his series of silkscreen depictions of former Chinese leader Mao Zedong (1893–1976), which he created in the early 1970s. Likely drawn to the subject due to the extensive media coverage of America’s new diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China at the time, Warhol created hundreds of images of Mao using as a template his portrait presented in the Little Red Book, also known as Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung (1964). Each of Warhol’s Maos is distinct—some ferocious, others parodic or beautiful—with the artist’s flamboyant brushstrokes often interpreted as a commentary on the resemblance of Communist propaganda to capitalist advertising. Considering the links between Warhol’s imagery and Chinese aethetics, Ai points out in his foreword that the anonymity that Warhol—as an influential contemporary art figure—experienced on his visit to China came as a shock.

Questions concerning the factors that led to Warhol to venture to China are addressed in a conversation between Jeffrey Deitch, former gallerist and director of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, and Philip Tinari, director of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. Deitch and Tinari recall that Alfred Sui, a young industrialist and millionaire son of one of Hong Kong’s finest families, had opened a new club showcasing popular international music, design, cuisine and contemporary art. A decision was made that an exhibition of Warhol portraits—including commissioned portraits of Princess Diana and Prince Charles—would be a fitting way to launch the endeavor. Warhol and a small entourage were invited to Hong Kong for the opening. On Warhol’s arrival, Sui surprised the group with a high-end trip to Beijing that was to include the Great Wall and the Forbidden City. Much to his disappointment, Warhol received no exterior portrait commissions for new work while in Hong Kong other then from Sui; the only art produced by Warhol from the trip, the book argues, consists of five stitched works, three drawings and the documentarian collection of photographs.

At the core of Warhol in China is the question of what merit, if any, these photographs present. The tome’s contributors present manifold arguments. Firstly, in capturing commercial influences in their subjects, Warhol’s snapshots succeed in their rich, documentarian approach. The popular fashions, slogans and advertisements of the time that he captured in the photographs are palpable today as symbols of a culture and time that has passed—a visual remnant of history.

The photographs also generate artistic merit in their reflection of Warhol’s preoccupation and fascination with patterns and rhythm. He seems enraptured with repetition, whether it be in the form of bricks, apples, stools, windows on buildings, posters that line the streets and so on. Even his interpretation of Chinese calligraphy was tied to an interest in recurring abstract shapes. In the five photos Warhol chose to copy and stitch together in quadruples, his ongoing affinity for complex patterns and visual rhythms is evident.

Above all, as the book’s title suggests, the photographs gain merit simply as a record of Warhol’s presence in China. Because the artist and the country are so different, readers are captivated—just as Warhol’s subjects appear to be—by his existence there. The portraits in the book, such as one of an elderly woman perched on a building ledge, or another depicting a group of Chinese men—some looking at Warhol, some looking away, one grinning, others perturbed—resemble the sort of image an anthropologist would capture on his or her first encounter with local inhabitants of a given place. Warhol’s subjects are caught unaware in their natural habitat, their faces ablaze with mixed reactions to the outsider photographing them. In many cases, as Tony Godfrey outlines, the photographs “constitute an especially interesting chapter in [Warhol’s] ongoing obsession with both looking and being looked at.”

Warhol in China enchants readers with a vivid vision of Warhol in 1980s China, poised behind the camera—a blue-eyed eccentric with his finger clicking away on the shutter.