-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

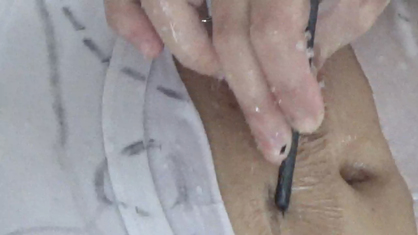

Installation view of MICHELE CHU’s Solace, 2021, wood, PVC pipes, metal, fabric, foam, dimensions variable, at “We Are Our Own Demons,” Negative Space, Hong Kong, 2021. Photo by Rave Wong. Courtesy the curator Clara Wong.

Five emerging Hong Kong artists were assembled by independent curator Clara Wong in “We Are Our Own Demons,” exhibited at Negative Space. Entering an intimate show addressing fragmented identities, memory, body, and self-consciousness, one’s own self-understanding was shifted from the outset by Wong’s request to remove one’s shoes. The visitor’s expectations of customarily detached art viewership were destabilized, and, moving into a gallery lit noticeably dimmer than a conventional white cube, one wondered whether one was actually intruding into a home instead.

Directly facing the visitor through the hallway was Ringo Lo’s Friend of the Birds (2021), a 1.8-meter-tall sculpture made of synthetic wig that extended nearly to the ground, with keychains of cartoon characters attached to glued cuttings of hair. The work references Lo’s own long hair, which has put him at odds with conventional presentations of male gender identity, and which alienated his mother but led to a strengthened bond with his grandmother. Hung behind was Lo’s Believer of the Fish (2021), a “tapestry” of fabric sheets, clothes, chains, and pins, featuring a pencil drawing of a Gundam. While the various keychains are from the artist’s own childhood collection, the drawing is newly drawn as an attempt by Lo to simulate and retrieve a “masculine” youth he never experienced. Together the fragments present both real and constructed memories, forming a pseudo-nostalgic patchwork of Lo’s self-perception.

Wong choreographs the visitor’s path through the gallery in a swirling counter-clockwise motion anchored by the Michele Chu’s Solace (2021), a large tunnel structure which physically dominated half the gallery. Invited to enter the work, one crawls into a curving, repurposed metal air duct. Unable to see the exit at first, one is enveloped by reflections and the reverberating sounds of one’s hands and knees striking metal surfaces. Looking up to see an exit opening into a cone of dark, netted fabric, one meets with both psychological and physical relief as headroom expands and metal turns to foam padding underneath. The piece is able to accommodate a range of interpretations depending on whether one is received by others at the exit, or emerges alone. Indeed, to participate by standing at the exit instead invites a fascinating inverse—rather than being the one who is transformed, one waits for another, wondering whether anyone will come at all. Filled with the hope that the tunnel’s reflecting shadows will materialize, this pregnant attending—all the more powerful if, à la Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1953), its resolution remains forever deferred—becomes perhaps more impactful than going through the piece itself.

One of two video works in the show, Natasha Cheung’s to study (2020) presents close-up shots of the artist’s body coated in gelatine, with the camera tracking a hand as it draws on her skin with charcoal. Reminiscent of lines drawn by a plastic surgeon in preparation for an operation, the close shots reinforce an impression that one is viewing a medical procedure—or perhaps an embalming. The disembodied hand that at first appears as foreign is in fact Cheung’s own, turning the operation into a self-dissection. Interpreting the piece together with those around it reveals latent themes of voyeurship and heightens questions of fragmented self-identity that complicate any initial reading of a simple act of drawing.

In contrast to many local artists who explicitly process Hong Kong’s upheavals since 2019, these works distinguish themselves by being introspective, personal, and meditative—making no reference to civil strife. This show presented a window into the emergence of a generation of young artists, with few or no recollections at all of the city pre-handover, reckoning with a quickly shifting socio-political environment. Alongside critical questionings of value systems, ideology, trauma, understandings of societal identity, and personal/collective consciousnesses, they are also grappling with received memories and constructed nostalgias—built from stories of a past transmitted from their parents’ and grandparents’ generations—while facing a murky and increasingly destabilized future. One left the exhibition reflecting not only on what the demons in the show’s title are, but who the “we” is, and what “our own” means as well.

“We Are Our Own Demons” was on view at Negative Space, Hong Kong, from April 10 to May 2, 2021.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.