R

E

V N

E

X

T

Without the Human: Book Review of Jungjin Lee’s “Echo”

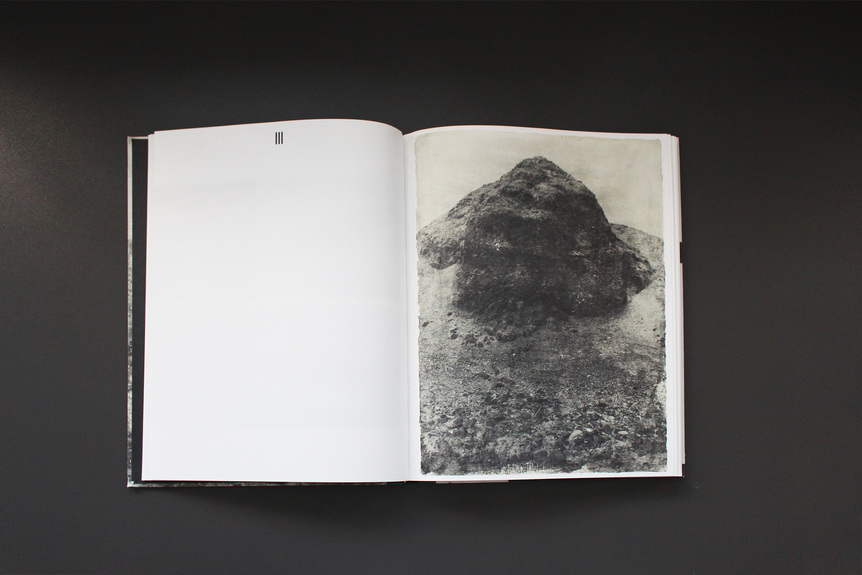

Echo by Jungjin Lee, published by Spector Books, 2018. All photography by Esther Chan for ArtAsiaPacific.

Jungjin Lee’s latest exhibition catalogue Echo (Spector, 2018) is a capstone on the Korea-born, New York-based photographer’s practice of more than two decades, during which she has built a reputation traveling the world, printing sparse, cryptic images in heavy monochrome on hanji rice paper, which she paints over with light-sensitive emulsion. Produced on the occasion of her solo exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, Echo races through Lee’s career. The photo sequences are terse and disorienting, jumping between her dramatic renderings of anonymous, anthropomorphic flatlands, shrubs, and rocks—which her mentor Robert Frank once called “landscapes without the human beast”—and motley still lifes, including pagodas, beans, and the handle of a mug.

It appears Echo’s primary objective is to offer a thesis statement for Lee’s ouvre. This is found within the book’s five essays, spanning 27 pages, in which curators and critics Thomas Seelig, Phil Lee, Liz Wells, Lena Fritsch, and Hester Keijser mount a familiar defense around Lee’s work: that the photography propounds “universal,” “transcendental” truths precisely because it contains so little content. According to these writings, viewers must not attempt to read Lee’s photos literally, or think of them as describing actual places. Rather, they claim in reverent, Orientalist tones, Lee’s practice of traveling alone to contemplate desolate landscapes—along with her rice paper technique—represent the “Buddhist concept of sunyata,” “the Hindu Prana,” the Korean concept of ki, or how she “through a Daoist-inspired photographic practice . . . dissolved the human being and nature.” As such, Jungjin Lee’s photography is “beyond logic;” it “evokes the human condition,” it is about “the infinite;” or simply “about nothing, or nothing much.”

The hand-waving references to Eastern mysticism are tiresome, as is the notion that non-specificity is what draws us closest to the “universal truth” of an object or landscape. In fact, Lee fits into the long tradition of artists who have transformed seemingly undefined tracts of land—including the American West—into surfaces for their individual desires, while glossing over concomitant histories of settlement and violence. That Lee disavows sociopolitical content in her pursuit of self-expression does not mean her work is not political. The exhibition for Echo included photographs from Lee’s series Unnamed Road, which as with her other landscapes, are arresting, emotive, and practically unrecognizable. As it turns out, Lee made these in Israel for the 2009–12 project “This Place,” organized by photographer Frédéric Brenner, who tasked Lee and 11 others with creating works for an exhibition that would picture Israel “beyond the political narrative” and uncover “the human condition.” No Palestinian photographers were included; Brenner explained that “anger” would immediately disqualify an artist from participating. Likewise, Lee explained in later interviews that she wanted to “look without too much information” and move her political feelings “to the back,” in order to present Israel as “a metaphor. Not as a representative of the real world, but rather as something that can be anywhere.” At best, this hazy universality—which wishes away borders, conflict, trauma—tells us very little about the human condition; at worst, it is a lie.

In this sense, Jungjin Lee has not so much become “one” with the world as she has—like so many photographers—flattened it in service of her own subjectivity. Far from overcoming photography’s metaphysical divide between subject and object, Lee simply reaffirms it. Perhaps critics’ insistence that Lee’s images are beyond analysis, that they embody the infinite! the human condition!—can be explained by a more practical concern: buttressing the rarefied position of art photography (that can be editioned, bought, and sold) from the rest of the medium, which may be no less “human”—but too topical, vernacular, and reproducible. Maybe this is why critics are especially eager to build myths around artists who are determined to retreat from the world into themselves, and can produce valuable physical objects to boot.

Amid photography’s unending visual conquest of the world, Echo is yet another album of souvenirs. This is not to say the artist has no right to them. But with the stakes set so high, it feels like a missed opportunity: for both Lee and critics to conceive of another kind of unification between subject and object, photographer and land—one that does not simply imagine closeness into being, but produces it through an unflinching engagement with history, place, and people. That is where photography finds its most human resonance—not when it echoes alone.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.