R

E

V N

E

X

T

Portrait of LEE KIT. All images courtesy the artist and Massimo De Carlo, Milan / London / Hong Kong.

“I’m not the kind of person who can conceptualize everything. I don’t want to,” Lee Kit said breezily when we met at Massimo De Carlo gallery to discuss his latest Hong Kong solo show, “The gazing eyes won’t lie” (2020). A painter by training, Lee takes an intuitive, Gesamtkunstwerk approach to his presentations, which emphasize the elusive and ephemeral connections that can arise within and between his mixed-media paintings, moving images, sound compositions, and readymade objects. Meeting as Covid-19 restrictions were easing up slightly, we talked about contemporary anxieties, staring at screensavers, and how Tinder photos are readymades.

The title of this show is based on a lyric from Interpol’s song “Narc,” which also inspired the name of one of your 2013 installations. Your use of the phrase seems ironic because you often engage with what is and isn’t visible, and with the trick of the gaze—in your practice, sometimes the gazing eyes do lie.

At first, the title for this show was “Embarrassed,” but then we found it too embarrassing to call it “Embarrassed.” I’m planning to use this title for a bigger show in the future. I considered, “Can I put everything I want to express in [the Massimo De Carlo] show?” Maybe not, because this is relatively small. So we kept the title for this show open, and then this lyric came to my mind, and I thought it fit the context in Hong Kong. With the protests, the pandemic . . . Like you said, the gazing eyes do lie. We don’t have time to gaze at anything. Everything changes so fast—information, news, everything happening on the street and in the government.

When I was in Europe in early March, I spent most of my time on my own, gazing—like sitting in a park, looking at nothing or at a dog. It felt very surreal, browsing Facebook, reading news about shit happening everywhere, including Hong Kong, while I was sitting peacefully in a park. It felt so strange but real; cruel, as well. Even though I wanted to do something, I could not. Even when I’m in Hong Kong, I cannot do anything. And I don’t want to [make art in which] everything is about politics or criticizing the government—I express that on my social media already. So maybe I can rely on just a gaze. It goes back to the question of “what can I do?” as an artist.

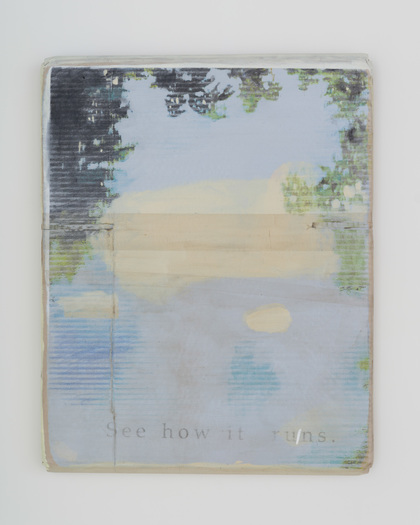

There’s a deliberate haphazardness to your compositions—ordinary words or images are displaced from their usual contexts and assembled almost as non sequiturs. In Landscape (I) (all works 2020), for instance, the phrase “See how it runs” is printed with no indication of what is running—it’s actually a slogan for table salt.

I have ideas but not a concept behind my works. I don’t want to control how people read the works or the exhibition. It’s boring when you go to a show and they provide wall text, and maybe there’s a person who tries to explain everything to you. If I’m the audience I just want to look at the show on my own.

How do you decide what to reveal and conceal?

It’s pretty random. I didn’t make a lot of work last year, since the protests [in Hong Kong] broke out. I wasn’t in the mood. I had doubts about everything. I spent time gazing at my unfinished paintings for weeks or days. At some point, I realized I was consuming them, gazing day after day until I didn’t even know if they were done. Then I started to erase or cover things. If I put tape there and it looked good, I would remove the tape and then paint the tape. I’m covering the paintings, thinking about how to finish it without thinking how to finish it, until there’s a point where I can sit and look at it peacefully. Or sadly! It depends.

Is there an undercurrent of anxiety in these new works? Texts such as “embarrassed” and “the voice in your throat waking you up at night” describe what people generally don’t want to feel.

Yes, we all understand anxiety. We all experience it—maybe quite a lot these days.

But it’s strange how the texts are paired with incongruously “happy” images, like flowers and a smiling woman doing yoga.

That’s the basic format. Everybody’s doing yoga or hiking, and artists are making landscape paintings or uploading pictures that look like still lifes. The woman doing yoga I think is from an ad on Facebook. It’s funny. That’s how people are dealing with Covid-19. I’m not being cynical or criticizing anyone. I’m just thinking of how I can adapt the format of an image and text, which is what I usually do. How can I make it a little different?

Stasis and motion relate in paradoxical ways in the video installation Chair mood, which utilizes jump cuts to show different positions of a chair in two settings—one brighter, one dimmer—but we never see the change occur.

For me that video is like a screensaver. It’s like gazing at a computer screen, not thinking about anything. I find that moment more and more difficult to encounter or to capture. We think too much these days, or we are forced to. We are bombarded by information or negative feelings. It’s really hard to look at a screensaver.

Chair mood can be kind of eerie. The image itself looks quite stereotypically beautiful, but it’s moving, it’s changing, without a sound. I think that’s how I’ve felt in the past few months. Wherever I’m staying, I have that kind of feeling—fearful and peaceful, it goes back and forth.

I don’t know if you’ve had this experience of being on your own and looking at a bottle of water for a few minutes, and the bottle seems to move or the size changes. I learned that actually it’s the movement of our pupils that makes us perceive this bottle as changing its size. Chair mood is a child’s game for me. I’m not talking about anything specific. I just tried to capture that experience, that kind of fear and quietness at the same time.

Blink and blank has overlapping snippets of music and birdsong that feel quite dreamlike. Could you explain the sound design of the work?

I thought, “I need to put some sound in this space,” just to keep people there. So I conjured some noises. If I simply incorporate everyday sounds and birds chirping, it becomes background, so I need something more. I could put in some beats or fragments of singing, but that’s too much. I can’t use a really strong guitar riff, like in Interpol’s song. I don’t have too many criteria for music, but it can’t be too strong or too soft. It should be beautiful, but not pretty. There might be some sounds that wake you up. It doesn’t need to be very memorable, but it might linger in your mind, like a dream or a sunny afternoon.

Could you elaborate on the distinction between pretty and beautiful? You often take appealing images—like consumer products in your earlier paintings or the woman in Text on the wall here—and turn them into something else.

Prettiness arouses temptation. It is ready to be consumed. Beauty makes you sit down and enjoy the moment; I think beauty actually takes you somewhere else, to a better place.

With Text on the wall, I found that image on Tinder. I’m on Tinder not looking for girls but for images. On dating apps, a lot of girls put up sexy images. But what other associations are there? What if she’s a protestor? You don’t “look like” a protestor. We can’t judge people by their looks. How can I capture something that is not in the image but is in my mind? Something between my perception and this image? That’s how I made that painting.

Images on Tinder are readymade objects. All my paintings are readymade objects. For me, there are criteria that make a painting a painting; for example, beauty, or a kind of everlasting feeling. You can gaze at it for a long time. Even if I could look at my painting for a long time, it’s still an object. I like to think about it in this way because then I feel like I own it somehow. Even if it’s a beautiful painting, I can still destroy it if necessary. I need to regard my works as readymade objects so I have the freedom to push them a little further when I’m installing my show. If you think about it as a painting, then you just think about where to hang it, where to give it a spotlight. I try not to use spotlights. For me, a show is not a show; a show is one piece of work.

What is the significance of layering many textures and surfaces in your projects? The video installations, for instance, are given further texture through the addition of a wooden panel, primed canvas, and paper, as well as the shadow of the viewer when they walk past the floor-based projectors.

My works try to trigger something. I’m my first audience because I install my own shows, and I enjoy seeing my own shadow in the space. It provokes something, it brings movement. If you want to escape your shadow, you have to move around—you’re kind of dancing, and don’t realize that you’re actually a performer. That movement is something that I cannot plan; if I did, it would be pretentious. That’s why I leave projectors on the floor or on top of boxes. Looking at my projection work is like looking at a painting. When you look at a very big painting, you want more distance. If you want to look at the details, you step closer. Sometimes, by putting a piece of painted plywood or a blank canvas in the projection, it looks like classical painting.

Do you choose those materials for your video installations intuitively?

Yes, I might already have the canvas or plywood, and I’ll hang it up and sit there for a few days just looking at it, consuming it. For some pieces I have a strong idea and I’ll prepare for it, like sanding a piece of wood for a week. So it’s a process of building up the confidence to finally project something on this piece of plywood.

Why is there a mug at the entrance?

I was finalizing the show, drinking coffee, and left that mug there. And Riccardo [Chesti, who works at the gallery,] asked me, “Is this part of the work?” I took it away. And put it back. Without it, the exhibition’s too clean. The mug is not going to destroy the beauty of it. Sometimes this happens when installing a show. If, by including something, the show looks and feels better, then it should be there. That’s the fun part. The only thing we did was wash the mug. The coffee is not part of the work.

Ophelia Lai is ArtAsiaPacific’s associate editor.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Lee Kit’s “The gazing eyes won’t lie” is on view at Massimo De Carlo, Hong Kong, until July 4, 2020.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.