R

E

V N

E

X

T

In his manifesto defending classical liberalism, “The Road to Serfdom,” Anglo-Austrian economist and philosopher Friedrich Hayek warned “of the danger of tyranny that inevitably results from government control of economic decision-making through central planning.” Aligning the economic power of central government with that of megacorporations, Maryam Jafri articulates society’s collective subservience and the capitalist power dynamics that govern these experiences, through video works such as Avalon (2011)—in which Asian female factory employees sew body bags and jackets that, unbeknownst to them, will be sold as fetish wear to Euro-American clients—to a project exploring the ongoing colonization of state independence by stock photo agencies, and her more recent installation works synthesizing the language of economics and politics into puzzle installations. Although the geography, subjects and themes are wide-ranging and disparate, Jafri’s narratives are connected by the same essential hierarchy of information and control, which uncovers the complex, interlinked mechanisms behind global patterns of consumerism, labor and agency, and the interstitial spaces that we—and the artist—might be able to occupy. On the occasion of Jafri’s comprehensive solo exhibition “Roads to Serfdom, Repaved,” mounted at Taxipalais Kunsthalle Tirol earlier this year, I reached out to the artist over email to engage in a conversation on capitalism, exploitation and the stranger-than-fiction elements that are inherent in her videos, installations and photographs.

In several of your video works, such as Mouthfeel (2014), in which two food industry workers discover their complicity in launching a food product that poses significant health risks, you seem to be hinting at the idea of transparency and choice being compromised in the larger engine of global production and consumerism. When did you first begin to explore this?

Avalon was definitely one of the starting points for me in exploring the role of complicity under contemporary capitalism. The increasing penetration by capital into all facets of life (think social media and the attention economy) and across all parts of the globe means we need a sustained critique more than ever, but it is a critique from within since, at this historical moment, not much lies outside of it and certainly not art.

Speaking of consumerism and generated trends, in works such as Wellness-Postindustrial Complex (2017) you pinpoint the collective desire to connect the body with the soul via traditional Eastern philosophies and practices, such as yoga and acupuncture. Yet in these sculptures we only see detached silicone limbs, an aesthetic at odds with holistic views of wellness and oneness. What drove you to assemble these sculptures in this way?

I believe it’s significant that the wellness trend is exploding at a time of increased social fragmentation, political crises and ecological collapse. People are turning inwards because they feel powerless in the face of all these challenges. The fragmented view of the body evoked by the various sculptures stands for the patient’s mind as much as his/her body and also for a collective body, a social body, in crisis.

Mariam Jafri vs. Maryam Jafri (2019), a video about Getty selling an image of your sculpture at Frieze art fair, explores copyright issues and artistic licensing. How did you come across this photograph, and what was your initial reaction upon seeing it?

Someone I knew had Googled me because they couldn’t make it to the fair and wanted to see what I was showing at Frieze. They then sent me the link, on the second day of the fair. I was shocked and annoyed but also oddly excited because I immediately knew what my next video was going to be about.

You see, in 2012 I did a series of works on how multinational stock photo agencies such as Getty Images and Corbis had been selling historical Independence Day images from African countries without adequately ascertaining if they actually had the rights to these images. The works in that series included Getty vs. Ghana, Corbis vs. Mozambique, and Getty vs. Kenya vs. Corbis, and in addition to the appropriation of cultural heritage, the works also focused on how often even the captions were incorrect—basic dates and names were wrong. Similarly, the caption accompanying the image of my work misspelt my name, wrongly writing Mariam instead of Maryam.

How did all of this translate into the resulting video work?

The first thing that struck me was whether or not I needed to actually pay for this image to use it—according to Getty Images I had to pay for it. The video explores the implications of what it means to license an image of your own work, a work that itself is in part a readymade and reflects upon the value of artistic labor—especially in the context of an art fair—and the relation between authorship and ownership.

With “Product Recall” (2014–15), you seem to be pointing at a specific type of American naivety, in which marketing companies have either grossly misread their consumers or the context in which their products exist. When I look at these objects, they seem almost like sculptures, with no real utilitarian use; I feel this way especially with the Pepsi nursing bottle. If you didn’t tell someone that these were actual products intended for mass use, I would even consider that these objects were made by yourself, the artist. Did you have a similar reaction when you came across these products, and if so, did that inform your relationship to them, and the real/fictional boundaries you explore in your work?

That’s a great observation. Yes, I am often drawn to things that are stranger than fiction, shall we say. But because so many of my works probe this border between reality and fiction, I am no longer surprised by it—I expect reality to be stranger than fiction.

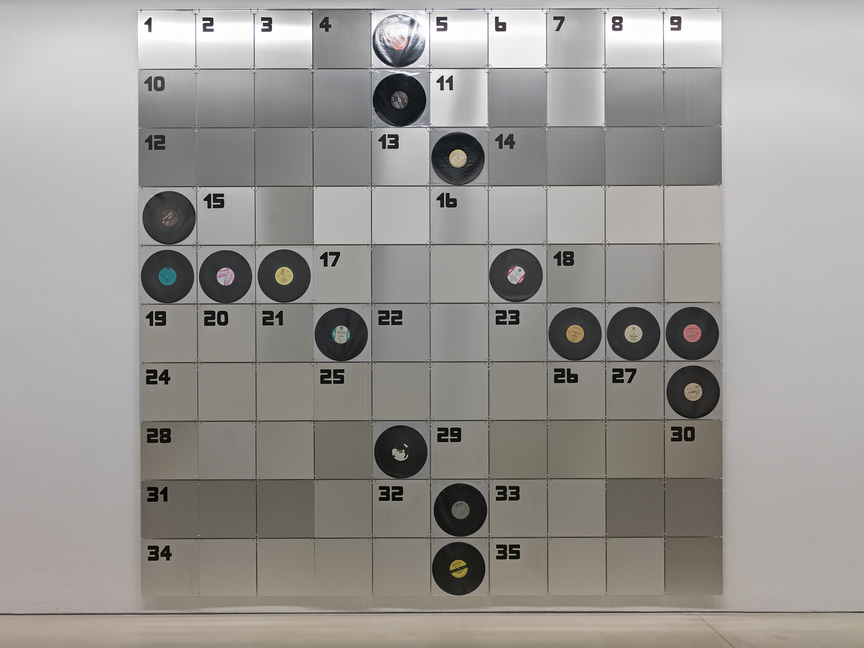

In the exhibition “Roads to Serfdom,” you left puzzles for visitors to solve. For example, Model 500 (2019), on the archiving of Detroit techno, and Where We’re At (2017), about how popular literature can reveal the American economic and political experience, both take the form of a sculptural crossword puzzle. How does the language of puzzle-solving relate to the ideas you set out in these two pieces?

In both works the clues are presented as vinyl text on the wall, next to the wall-mounted sculptural puzzle. The clues help frame and contextualize the sculpture, almost like an extended caption. The text can be ready poetically, as short phrases that set a mood or a tone, and thematically relate to the LPs or books that are integrated in the sculptures which themselves contain text in the form of titles or phrases. Language is often an integral component in my work, whether with vinyl wall text, a voiceover for a video, or a caption for a photo. However, the clues are also functional—the puzzle can be solved. Thus the work is anchored in history and implies that there are important questions with right (and wrong) answers, because even in this era of data fog, alternative facts and fake news, some data are more useful than others, some facts matter more than others, and some fictions are more inspiring than others.

With this much misinformation, is it possible for us to make better choices?

I think we can, or else I wouldn’t work with this theme. It’s also important to look to the future, to keep the flame burning so to speak, even if, in the short term, things seem difficult and no solution seems forthcoming.

Maryam Jafri’s “I Drank the Kool-Aid But I Didn’t Inhale” is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, until June 30, 2019; and “Automatic Negative Thought” is on view at The Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, from July 5 to September 22, 2019.

Ysabelle Cheung is managing editor at ArtAsiaPacific.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.