R

E

V N

E

X

T

Based in a studio to the west of Shanghai’s city center, painter Su Xiaobai has been described as being hermitic. It is true that Su mostly avoids publicity and the courting of collectors that is today a seemingly fundamental component of artistic production. However, on arriving at his work space, what I found was a small commune with a contingent of workers.

Su oversees a complex process, which simmers somewhere between mass production and craft. The afternoon that Su showed me around, a host of assistants reinforced the impression of a Medieval printing workshop, laboring over the various stages of Su’s large, layered canvases, each lozenge-like form being passed from one station to the next until they enter the main studio, where Su applies coats of lacquer, until the object itself recommends its completion.

It wasn’t a simple journey to this point. Born in 1949, Su studied painting at the Wuhan Institute of Painting, and the Hubei Institute of Fine Arts before attending the Beijing Central Academy of Fine Arts. Like many of his generation, he left China when he was offered a scholarship; in 1987, he was accepted to the graduate program of the Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts in Germany. There, he immersed himself in Western art, forgoing the skills he learnt in Beijing.

After 15 years of living and working in Europe, he finally returned to China, where he began his experimentation with traditional lacquer, which led him on an investigative journey to over 20 Chinese, Vietnamese and Japanese lacquer workshops as he refined his skills. Pairing these traditional materials and techniques with his knowledge of Western abstraction, as well as a particular love of Mark Rothko’s works, Su began to investigate not just the nature of the painted surface, but also the potential space that painting can inhabit. Tentative experiments with shaped canvases soon developed into his signature style of “space occupation.”

With his first major institutional solo exhibition “And There’s Nothing I Can Do” opening at Kobe’s Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art in a matter of weeks, Su and I sat down to discuss his work history and its potential futures.

It has been observed that your practice has passed through three stages, from social realism to abstraction, and finally to the exploration of lacquer. What was it in this journey that led you to lacquer?

Actually, from the beginning, social realism wasn’t my choice, but because of the social reality at that time, all artists practiced the same style. It wasn’t my skill or speciality, but it was necessary, and in fact it was a burden. During the second phase, when I moved to Germany and continued my studies in painting, I encountered all these great masters, but even that was not really my choice. I stepped into abstraction because it was what surrounded me, it was my environment. What really was my own choice was the third phase—lacquer.

So the third phase was when you found your voice.

Yes, and I felt that I was old enough to find my voice! For the first two phases, I just went with the flow. All of that history is part of my journey, and my artistic capabilities come from all of those experiences, but I had come close to giving up—until I found my freedom, my own state to express myself.

My next question was going to be if you envisioned another stage, but I feel I should cross that question off. From what you just said, it seems you feel that there doesn’t need to be anything besides lacquer for you. But if you examine the titles that you give to your works, many of them touch on Chinese history, which goes beyond lacquer. There is a wider nostalgia. Gao Minglu, the art historian and scholar, also mentioned in his catalogue essay, “True Sequester Lies in the Madding Crowd, True Pleasure Lies Within the Work,” written for your upcoming exhibition in Japan, that for you, lacquer is similar to literature. This intrigued me, as it seems to me that the literary processes—construction, layering, editing, erasure—are perhaps, of all the arts, uniquely shared by painting. Could you explain more about your ideas of the shared qualities of lacquer and literature?

I like Gao’s comments on this point. When I am not painting, I am reading, and as you said, there is a process that is similar between my art and literature, this process of layering and editing. That is what Gao alludes to. He also positions my work as “high art.” I would agree, but those are ultimately his opinions, and they’re not things that I consider when I am making art. I don’t really care to explain my work in those terms.

In Gao’s essay, there was a reference to several works that had literary titles, but my feeling is that you let your process develop, and that naming the works is a process of reminiscence, a nostalgic act. Would you agree with that assessment?

Yes. I admire Gao, we are the same age, had similar experiences, and we speak often, but for myself, I have no great mission. I simply communicate my life experiences through my practice and materials. In the past three years in particular, I have felt confident, strong and stable: I come to my studio, I work, and I feel calm. My work doesn’t strive for narrative in the way that Gao suggests, but his interpretation is nonetheless valid.

Every artist is different, and some need to work with dramatic circumstances, with chaos around them, but for me, the most important thing is peace and stability. Do you know the David Bowie song “Space Oddity”?

Yes, of course.

It describes this moment when an astronaut comes back from space; he sees the beautiful blue Earth from above, and says that there is nothing he can do. It is a powerful moment, because you have no control but you see everything, and it’s beautiful. I strive for that moment in my practice. That’s why I used “And There’s Nothing I Can Do” as the title of my upcoming show in Japan. It also connects to my time living in Germany, because Germany’s modern history is full of turbulence.

What you describe is an interesting position for an artist to be in, because, particularly since the beginning of the 20th Century, people have been obsessed with this notion of progress.

Especially in China! It is interesting that a lot of people comment that my work has this old, oriental feeling, and of course Chinese traditions inform my work and are part of my history, I don’t deny it, but that is all surface. The underlying truth is that I work each day for good moments. I don’t work aggressively. I just enjoy doing my work peacefully. It’s funny, because when I am in Germany, people comment on the Chinese nature of my work [because of the medium of lacquer], but when I come back to China, they say you‘re so Western, it’s so German [because of the abstract compositions]! So, I identify with the German notion of heimatverlust, homeless-ness: I have no hometown, but I embrace it. I like being in between East and West. It can be good to have these antagonistic elements.

I want to discuss the physical form of your lacquer paintings. Some of the pieces appear to penetrate into the wall, and some curve out into the space between it and the viewer. There is a particular philosophy about removing the frame from paintings, which developed out of the ideas of the political aesthetics of the 1950s. The idea was that the frame was the border that separated the artwork from the world, and without it the work became a part of the world. It seems to me that your work takes that a step further. I wondered if you can discuss how you first decided to work that way—what motivated you to work with three-dimensional expressions?

The process started gradually, but from the beginning I felt that there was a weakness with my works: because they are abstract, there is no depth. Traditional painters set up three-dimensional spaces within two-dimensional surfaces but my work does not have this, so I started to think perhaps I could physically occupy space. The first iteration of this idea was influenced by traditional Chinese roof tiles, with their curves, so I experimented with that, and then it developed over time.

As a consequence, there is a particular tactility to your works. And, besides touching, there is something in the shape that makes one want to smell it!

Absolutely! Even when I am making them I have that experience! That reminds me of what a curator said at one of my shows in Germany. According to him, my works evoke the same impulse that a parent has to stroke their child’s face, full of love and desire to connect with the world.

Finally, can you tell me about “And There’s Nothing I Can Do” and what the audience can expect? I assume that it is not a chronological display, so how did you select the works for the show?

I got quite anxious about it and I couldn’t sleep! I needed to know more about the museum space, which was designed by Tadao Ando—this is the second time that I have exhibited in an Ando-designed venue, the first time was in 2010 in Germany—as I wanted to make sure the works and space would be complimentary. So Ando’s studio sent a designer to work with me. He visited my studio and took many notes about my work, writing them on his hand. He broke the exhibition space up into three areas, and I made a scaled down model of it [to help plan the layout of the show].

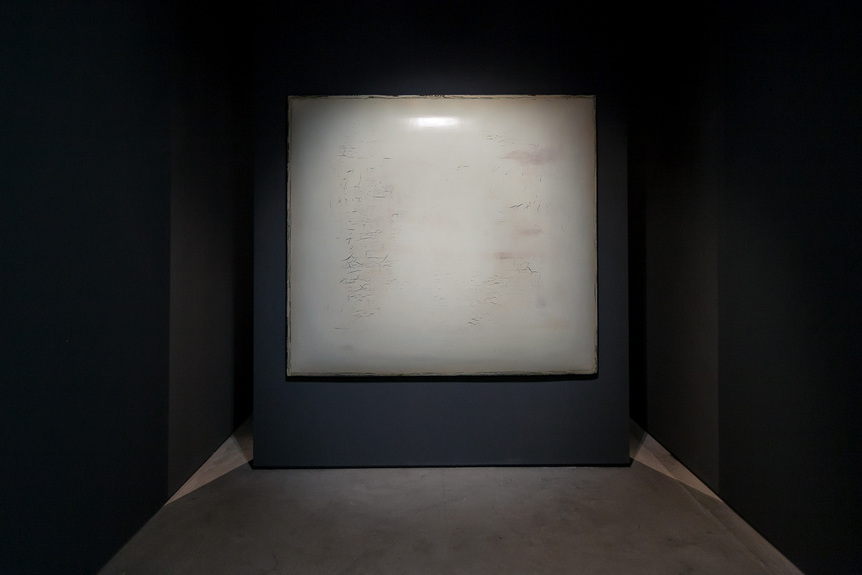

My exhibition will be quite dimly lit. Originally we wanted a James Turrell work to be part of the display, and the layout was planned with that in mind, but that didn’t work out. At the same time the museum will have a show of paintings by Diego Velázquez from the collection of the Prado Museum in Madrid. I am honoured to be on the same level as Velázquez! I came up with the layout with his work in mind also.

It sounds like a collaboration between the architecture and the artwork. Ando’s spaces are all about light, contemplation, and spaces of reflection, and your works are very much in dialogue with that. But also, Ando’s spaces are, in a sense, quite intimidating, especially for art.

Yes, I started with 50 artworks and finally we chose 25 paintings for the exhibition, but I think the space and works compliment each other. I am both excited and nervous to see the show in the real space.

Su Xiaobai’s “And There’s Nothing I Can Do” opens at the Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art, Kobe, on October 12, 2018, and will be on view until November 28, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.