R

E

V N

E

X

T

Liu Jianhua was one of the first Chinese artists that I met when I moved to Shanghai in 2016. By coincidence, he had just returned from my hometown in New Zealand where his exhibition, “Transfer” had opened in February that year. Seated together at a dinner, we spoke at length about his time in New Zealand, and despite my terrible Mandarin, we discussed doing an interview for a book I was planning. The book didn’t happen and the interview didn’t take place until we met again in the summer of 2018 and he reminded me of it. Liu is one of those people who emits calm and befriends everyone. As my taxi pulled up to the gate at his Shanghai studio complex in August for our long overdue conversation, the suspicious demeanor of the guard melted like butter when I explained who I was there to see. “Please go inside” he smiled, “don’t keep teacher Liu waiting!”

The details of Liu’s early life are well known. He was born in Ji’an, Jiangxi Province, in 1962, and followed his uncle to Jingdezhen—a town famed for its ceramics since the first millennium—at the age of 12 to study ceramic making. Two years later, he began an apprenticeship at a local pottery factory, learning all aspects of ceramic production. His accomplishments were soon acknowledged by China’s top prize for ceramics, the Hundred Flowers Grand Award for Chinese Arts and Crafts.

In 1985, following the end of the Cultural Revolution, Liu decided to enter university and was admitted to the sculpture program at the Jingdezhen Pottery and Porcelain College. During his time there, he was determined to use materials other than ceramic, which he had come to resent from his early years, and experimented instead with plaster, fiberglass, wood and steel, among others. Later, however, as his practice developed and he began working with figuration, particularly with figures wearing traditional qipao dresses, he returned to clay as a matter of utility—the silken result he desired was most easily achieved with ceramic.

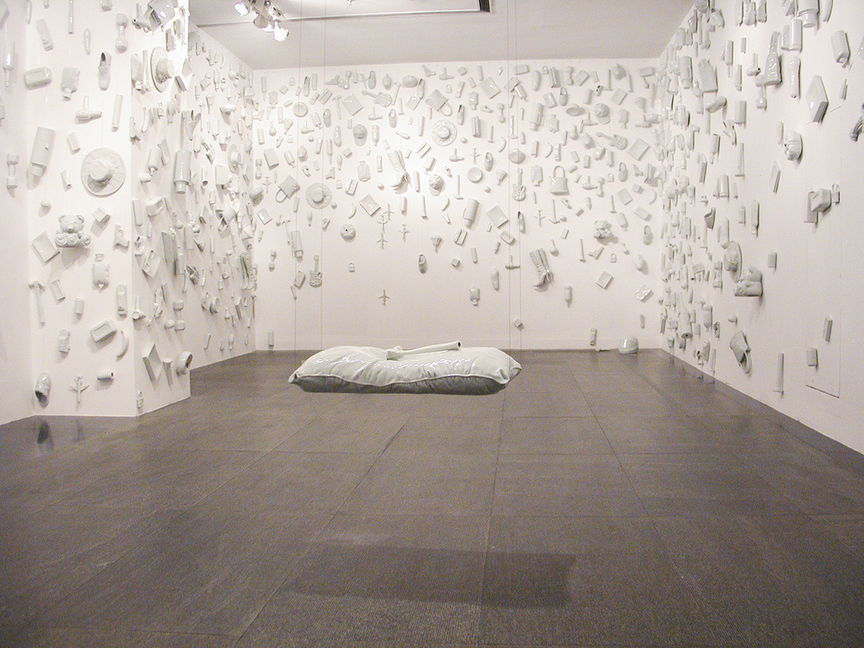

Since the inclusion of his ground-breaking series Regular Fragile (2001–03), a collection of more than 1000 prosaic objects recreated in pristine white porcelain, in the inaugural presentation of the Chinese national pavilion for the 2003 Venice Biennale, his career has been on the ascent, and he has been included in numerous international biennials and important survey exhibitions of Chinese contemporary art—despite how the 2003 Chinese pavilion never actually made it to Italy. Given his recent inclusion in the 2017 Venice Biennale, we decided to frame our discussion of his most interesting career within these two Italianate bookends.

Speaking of Regular Fragile, my understanding was that the Chinese pavilion presentation never actually made it to the Venice Biennale, and the only place where it was seen was the Guangdong Museum of Art in Guangzhou. There are a couple of things that I wanted to clarify: was Regular Fragile made specifically for that show, and did it ever make it to Venice?

Firstly, I should explain how I made Regular Fragile. In 2001, my son was six years old. He had earlier been diagnosed with asthma and we had to go to hospital every month, which made me feel quite helpless. Everything in the hospital is pale white and fragile-looking. That year, there was also three plane crashes, and I thought a lot about how I would be affected if my family were on those flights. There was one flight in particular with a group who were on their way from a little girl’s birthday party in Beijing, and the pictures from the crash showed the remnants of their gifts floating on the water. It was very touching and made me think a lot about the fragility of human life. These experiences all contributed to Regular Fragile. I wanted to make something about those objects, about things from daily life. So the work wasn’t made for the Venice Biennale, it had been seeded before then.

The story with the 2003 Venice Biennale is interesting. It was the first year that China was meant to have an official pavilion at the event—five artists were to be featured—but unfortunately there was also the outbreak of the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) epidemic that year. After much speculation and uncertainty, we finally got a decision from the Cultural Ministry: no, we weren’t going to Venice. However, then, after discussions with FransescoBonami, the artistic director of the Biennale that year, it was agreed that the Chinese pavilion could be held in Guangzhou at the Guangdong Museum of Art instead. It was the only time that a national pavilion was allowed to be outside of Venice. It was nevertheless still hugely disappointing for us that we weren’t going to be in Italy.

Many of the reviews about the Chinese pavilion were very positive. More importantly, they claimed that it was that very exhibition that brought your work to international attention. Would you agree with that argument?

Yes, the exhibition in Guangzhou, titled “Synthi-Scapes,” attracted a lot of attention and garnered great media coverage. That exhibition was probably better promoted and drew more attention than my participation in the 2017 Venice Biennale.

To reiterate, however, we never went to Venice for the 2003 biennial—we never even went to check the venue. I remember clearly, it was before the Lunar New Year and I already had finished part of Regular Fragile. I had an idea of what I was going to do and I had a sense of the space that the work was going to be shown in, but I never went to the actual site. I think the curatorial team went to check the venue, but none of the artists did.

So, fast-forward to 2017, and you’re invited to be part of Christine Macel’s “Viva Arte Viva,” the main exhibition at Venice, with the work Square (2014), a multipart installation of gold-covered ceramic droplets on square, steel plates. How did you become part of that show?

I was in London for the installation of my work at the Victoria and Albert museum and I got an email asking me if I would meet with a curator. I knew nothing about it at all, but I said, yes, let’s meet. So I met with Macel, and she asked me a few questions. Then she came to Shanghai and visited my studio. Before she came, I saw the news that she had been appointed curator of the Venice Biennale, but I didn’t recognize the photo in the article so I didn’t realize it was the same person!

I actually don’t know how she found me, so when she came to my studio, I showed her around, and she asked me a lot of questions about Square. I suggested that it could be presented on a large scale, as what I had there was just a small section. It was all very mysterious as to why she was interested in my work. Then we sat down, and she said, there’s an exhibition I’m working on. So I laughed, and I showed her the article and I asked her, are you talking about Venice? Then she said yes. From there, we began to discuss the Venice exhibition. We talked about the display space, which would be shared between me and Polish installation artist Alicja Kwade, and from there it happened very quickly. I was very happy. I liked the room because the other spaces in the Arsenale are very dark, but that space was full of natural light.

At some point Macel broke up the various spaces into separate pavilions, and your exhibition space became known as the Pavilion of Time and Infinity. Did you discuss that concept and how your work fit within that?

Yes, my work was about time, space and human nature, so I think that perhaps the pavilion concept came from my work. I think that it worked well. For me, ceramics and steel are both time-based processes, and are related to temperature and burning. There is a contrast between the two however. People see the strength of steel and assume that it lasts forever, but actually it gets weathered in nature and has a very short life compared to ceramics. Ceramics will last for thousands of years, but there is a perceived fragility. There is a sense of conflict between the two.

Between these two seismic events—your participations in the Venice Biennale—there was a point in 2008 where there was a change in your practice. Before then, you were interested in social issues relevant to the changes in China, such as urbanization and environmental damage, and after that, there was a focus on abstraction, which you explained as having “no meaning, no content”—was there something that occurred in 2008 as a catalyst for this change?

Even before 2008 there were some changes. I moved to Shanghai—a massive city—in 2004, and I was overwhelmed by it, so that had an impact. In 2005, I was already trying different things—ready-mades, for example. After 2008, instead of looking and commenting directly on social issues, I switched to a more distant and objective perspective, and left more room for imagination and reflection for the viewers. My minimalist approach has close connections with the abstract forms of expression deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture. It was an attempt to explore the relationship between traditional and contemporary artistic languages so as to trigger an explosion of new ideas, and ultimately, to develop a personal system of expression. Also, beginning in 2008, I had some health problems. Shanghai became a blender for all of these factors.

So 2008 marked not so much a complete revolution in your thinking as a turning point in what had been a gradual transition?

Yes, of course. All my work from around that time was fragmentary. When people write about it, it seems much more linear, but it wasn’t so considered. It happens as it happens.

What are your future plans?

I have several important upcoming exhibitions, including a solo project in Naples opening on December 7, called “Monumenti” and a massive group exhibition of minimalist art, called “Minimalism: Space. Light. Object,” opening at the National Gallery Singapore on November 16, as well as “Heimat,” the 2018 Guang’an Biennale of Work, which opens on December 16 in Guang’an, China. But I’m busy all the time. Even if I don’t have a project, I’m always thinking about how to move forward, to create new work.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library