R

E

V N

E

X

T

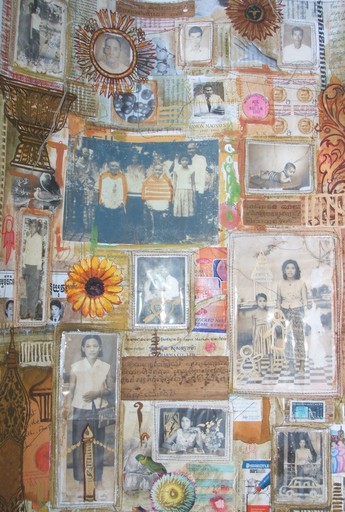

Several blocks away from Phnom Penh’s Royal Palace and the Supreme Court is self-proclaimed “freedom artist” Leang Seckon’s three-story apartment-cum-gallery. Leang has dubbed this space “Mutrak,” derived from the Sanskrit word “mudra,” a symbolic, ritual gesture in Hinduism and Buddhism. Mudra is one of the most significant elements of traditional Buddhist iconography, denoting meaning in images of the Buddha and sometimes indicating a specific moment in the life of the historical Buddha. For Leang, whose practice spans performance, painting, sculpture, installation, and text, artworks are mudra—gestures in which meanings are communicated. Focusing on themes of reconciliation and transcendence in Cambodian cultural and sociopolitical history, Leang often incorporates autobiographical perspectives that nonetheless speak to a wider national collective memory.

On the third floor of Mutrak is the inner sanctum, Leang’s personal quarters, decorated with gold murals that he had painted himself, depicting characters from an unpublished novel he has been working on. In the dramatic and regal setting of the artist’s living space, punctuated by an altar of eclectic items that he had collected or crafted and heavy curtains recalling theater drapes, Leang and I sat down to discuss his inspiration, his use of Khmer iconography, and the connection between his poetry and his art.

Your first solo show, held in 2002 at Java Café and Gallery [now Java Creative Café], was called “Apey Mutrak,” a Buddhist blessing of peace and courage. This Buddhist reference also appears in the name of your studio, Mutrak. What inspired you to use Buddhism as a subject of your art?

That show was about the Buddha, but from a new perspective. For ten years in school, I learned drawing, traditional painting, architecture, and interior design, but school alone does not make you an artist; there are other aspects that influence you. I thought about this influence, and Buddhism is one of them; it is like the roof of your house. Growing up during and after the Pol Pot era, there was no art. The art that I saw first and foremost was the art of the pagoda, the Buddhist mural paintings and their narratives, and the prayers that the monk recites. I wanted to explore what I saw and use it in my own way. With Buddhist aspects in mind, I began to ponder on materials, gold foil, saffron robes, incense burners, candles, and other Buddhist-related materials and sacrificial objects. I take these objects and materials and see how they can be used for my works.

“Apey Mutrak” was sold out. Some works were purchased by Kong Sam Ol, the minister of the Royal Palace!

Your creative process involves various mediums and techniques, including recycled materials. I’m particularly interested in your use of the floral-printed textile, sarong. What inspired you to experiment with it?

I had a three-month residency in Fukuoka, Japan, in 2009. For the residency, I created a big dragon—it was impressive and I liked it. It was a continuation of my previous work using recycled materials to create a gigantic naga (“serpent”) in Siem Reap. But more and more, during the residency, I wanted to do something more personal, autobiographical. I began to ask my family about the civil war in Cambodia. Through many conversations, my mom told me about her heavy sarong skirt. She told me that it was an old and torn skirt, and since she had only one, she needed to patch the ripped parts, so over time, it became heavier. I was drawn to this idea, and asked her to remake one skirt for me. Heavy Skirt is a story between me and my mother; the skirt was used when she was pregnant with me, it protected me from the [American] bombardment. Since [I learned of the skirt], I began to use the floral motifs on sarong for my next work, and later the whole sarong itself. It became my signature. Sarong is my motherland, from where I was born and creativity flourished.

You integrate animal hide into your work, which can be traced back to Sbek Thom, Khmer shadow puppet theater. When did you start using the material?

My works in general are always interconnected, but they progress like steps, they keep changing from one moment to another. I used hide before, but in a small scale and not in the form you see today. I reconnected with the hide again when I was traveling back and forth to Siem Reap, because I have a house there. I often visit the Khmer temples when I am there. And more and more, I became interested in the idea of repatriation, the return of the Khmer diaspora and the return of Khmer artifacts. One day in Siem Reap, I saw the carving of the hide into shadow puppets. They spoke to me; it was as if they had life. Then, I thought to myself that the returned Khmer sculptures have life, too. From there I began to explore the hide as part of my work.

You write poetry and songs as well. How does text intersect with your art, or are they completely separate?

My painting is like poetry. I want my texts to come to life in my painting. My art and poetry are intertwined and have same [character]—they are multifaceted, metaphorical, and never direct, and they could be about social, economic, and political issues and all aspects of life in Cambodia. My paintings can be replaced by my poems, except the paintings are visual. When you read my poems, you will have a better understanding of my paintings, too. I sometimes take an excerpt of my poem and write it onto my painting, and some aspects of the painting are sometimes inspired by the poem.

I understand that your texts sometimes include Khmer inscriptions, which you are also using in your current work. Could you please elaborate on that?

I like Khmer [stone] inscription. I like the Khmer script from the pre-Angkorian and Angkorian times. They are beautiful, and they are like paintings—they are artworks in themselves. For me, text is very important, it has its own life. It is also art, and a path to guide you somewhere. It’s like how people tattoo their skin with Khmer script. It is both for body decoration, like an ornament, but also for protection, from danger. Khmer script has a magic power.

I am currently working on a project called Prah Kumadeng, which is a Khmer word that refers to those who create, lead and have the power to influence. I believe artists could be included as Prah Kumadeng because of their talents to create. In this series, I make paintings, I wrote a poem, and lyrics to more than 20 original songs. I also created the music for these songs and I will sing them myself. I will select some songs and carve them on a stone slab like an ancient inscription. This series is different from my previous ones.

Because you use traditional Khmer materials and iconography, some people claim that your work is not contemporary at all. What is your response to this?

I think they need to understand and learn what “contemporary” is. Each country, whatever that country is, has its own idea of “contemporary” and its own way to progress and move forward. That step is already contemporary. Materials are a way to form ideas and image—hide does not only mean a traditional Khmer puppet. And my works embed a lot of contemporary narratives. All of those things combined make my work contemporary.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.