R

E

V N

E

X

T

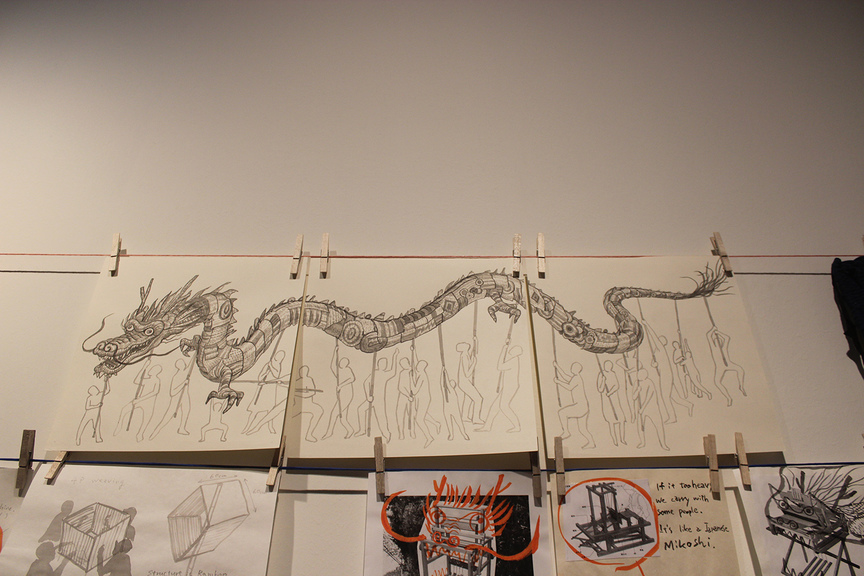

Occupying the main gallery at The Mills—a former Tsuen Wan textile factory converted into a base for Hong Kong’s soon-to-be-launched Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile (CHAT)—is a colorful dragon with a head resembling a loom and a body made

of bamboo and recycled clothes, poised to swoop into the air. This

is a project led by Berlin-based Japanese artist Yukihiro Taguchi,

whose site-specific works are not only spontaneous multimedia experiments, but also ingenious responses to time and space. He joined CHAT’s residency program in 2016 and this summer, as part of a series of textile-based public workshops, Taguchi collaborated with Hong Kong fire-dragon-dance master Ng Kwong Nam

and Tsuen Wan locals on the performance-installation Spun Dragon (2018), highlighting traditional craftsmanship and deepening our visions of community.

I met Taguchi at The Mills several days after the dragon dance, where the woven dragon figure that he and the local community had been working on was officially put to the test. We discussed the development of Spun Dragon, his use of recycled materials, and how his artistic practice brings people together.

Your installations and stop-motion videos are often whimsical creations that animate and at times subvert a static or familiar environment. What drives you to create these performative assemblages and videos?

I have been making videos for more than ten years now, but at the beginning, it was photographs. They were originally taken just for documentation, because after an exhibition or a project, my installation works would not exist anymore. Many of my works cannot be kept. They would be destroyed, thrown away or disappear. That’s why I think documentation is important.

What is it about stop-motion that appeals to you? Does it inform how you create your installations?

A photo can have nice composition and colors. When I take many similar photos and preview them, it becomes a short movie. Then I thought it would be nice to make not only an installation, but a moving installation, like it’s alive. That’s why every time during the making of the work, I move, shoot, move, shoot . . . At the end, it becomes stop-motion video.

Why did you begin to use recycled waste as the primary material for your creations?

If I buy materials from the store, it’s just money. Maybe I know the shop, but there’s not much connection. But I have a closer relationship with the donator [of used materials]. Even for objects that I find on the street, they carry stories, which become a part of the artwork.

When people look at them, they can think of similar situations [involving those objects] that they once had. For Spun Dragon, if you’ve experienced working together to weave, you would think about those moments and be touched by watching the video or the piece. Material has this power, I think: it triggers your memory and you can share the memory with the material.

Human Weave (2018) shows five people standing in a line with strings tying them together like a knitting pattern. When I think about the cultural meanings of strings and knots, I think of en (縁), the connection among people. What is the role of community in your works?

For me, this work is a metaphor for weaving. Each person is like a needle, or like time. The timeline stretches vertically; we all have personal time, and it grows. For example, this is Yukihiro Taguchi standing in the middle, and my past [from the ground] stretches upwards to the future . . . If we put them together, we will get a fabric, woven publicly. There are many possibilities for this fabric—you can make it into a bag or clothing. It’s the same with community: one person can be weak, but with five people, it’s stronger. This is the concept that this performance is trying to explore. It focuses on weaving and what weaving means to me.

You highlighted the color red in this work. It reminds me of the Red Thread of Fate that connects people in traditional Chinese culture.

Yes, red is also associated with blood. For this video, I didn’t do stop-motion or slow motion; I didn’t really touch it, but only changed the color of it. This video was created around the same time as the dragon, but I had already thought about this metaphor two years ago, when I became interested in weaving.

In using recycled materials, you’ve allowed a certain degree of unpredictability into the work, especially in the texture, look and color of the fabrics. As a result, Spun Dragon looks very different from a traditional dance dragon. How do you arrange these materials to create a work according to your vision? Is control an important aspect of your work?

In the planning stage, we changed a lot of things. I talked with curator Him Lo and the staff at CHAT. There were two versions: this [three-dimensional] one, andthen there’s also the flat one, which is easier for showing the weaving, but when we put it together, we realized it was difficult to carry. Sometimes, if [the performers] walked fast, it would break easily. It’s not flexible enough. That’s why we thought we should separate the body of the dragon into pieces, like leaves. This time, we came up with the idea that the dragon can be a loom. I tried making the loom look like the face of the dragon. By doing so, the idea of weaving connects with the dragon in a better way. This [leaf] shape looks like the shape of Tsuen Wan on a map. Later, I made this structure in Berlin, a test piece. The problem was when we carried it, people could not see so much [detail] unless they saw it from the top, so eventually we decided that a three-dimensional version is better. We tried different shapes. The round one comes from the idea of the yarn, but you cannot really see the top of the shape. In the end we found that the cube is the best because you can see every corner from the side. It’s also easier for each person to work and weave.

As for the color, we had some problems at the beginning. We got a lot of clothes, but most of them were in dark colors—black or grey. Later we got some other combination, and we started to have some colorful shirts. The arrangement is random, since we wanted more color variations. People can choose their colors as they like it. It’s also interesting for me to tell which colors are their favorites. So there’s not much control, but we prepared for as many variations of colors as we could.

Spun Dragon marks your first time working with a master of traditional fire dragon dance. Also, for your work Okurimizu (2018) at Echigo-Tsumari Art Field, you made use of miso barrels. When did you begin bringing traditional elements into your work, and why was this important?

When I started to think about the dragon, I thought about what the dragon is, where it comes from, and what its history is. Naturally, I thought about tradition and how it’s better to learn from it. I studied oil painting [at university]; even when I paint, I think about the reason and the history of it. Behind these materials and characters, there is something traditional or primitive. For weaving, it seems simple at first glance but whoever came up with this technique in the first place was very clever, right? For the dragon, it’s the same. I also respect the dragon master. He has been doing this since childhood, now he wants to share the culture of the dragon with people. I can feel his passion.

I think from there I can learn more.

You’ve traveled to many places. What is the relationship between location and your creations?

I have always been thinking about this. Recently, I think my job is to connect something. I’m like glue, you know. After the connection,

[my work] also moves and pushes things along. I don’t touch the dragon anymore now, but other people can continue to develop the woven dragon. My work is to build relationships between people and materials, or place and materials, or place and place. When you connect, things can be changed in a profound way, like when I put the installation on the street, it becomes a landscape. This time, we changed the simple act of weaving into a dragon. The idea of change has always been a main concept of my creations.

What are your future projects? Are there any specific places that you would want to explore?

I do have projects coming up in Berlin and Japan again, but in the future, I want to go to Sicily. I got married last year and my wife is Sicilian. I’ve visited several times but I’ve always thought that I should do something there. I don’t know what the project would be. As always, I have to react to the location and the people there first.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Pamela Wong is an editorial intern of ArtAsiaPacific.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.