R

E

V N

E

X

T

The 84-year-old Fong Chung-Ray was an early pioneer of contemporary Chinese art. Born in Henan province, Fong joined the army as a teenager, following them to Taiwan where he received art training at the military’s cadre college. After leaving the army, he became a key member of the Fifth Moon Group, who represented a new wave of modernism in Taiwan in the 1960s. In 1971, Fong was awarded a grant by the John D. Rockefeller III Foundation, enabling him to travel across Europe and the United States. His exposure to Western art during that time shaped his aesthetic sensibilities, leading him to his original abstract visual language that draws from both the Chinese ink tradition and modern Western art. Shortly after his stint abroad, Fong immigrated to the US, settling in the San Francisco Bay Area

where he has been based since.

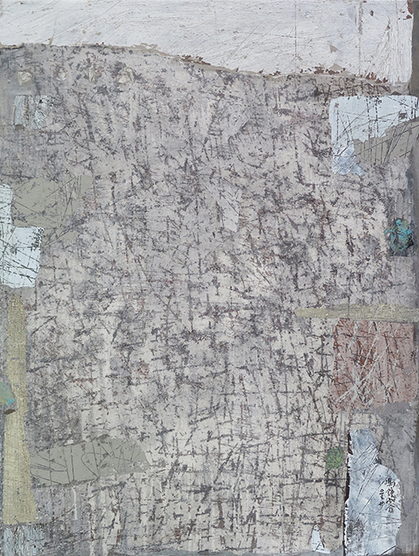

Fong’s early works are characterized by loose forms painted freely with ink, acrylics and watercolors using coarse palm leaves tied into a brush. Over the last two decades, however, Fong has increasingly used collage to create his art, developing an unorthodox technique where acrylic is applied onto thin sheets of plastic to produce patterns that are then transferred onto paper or canvas. He also often incorporates Chinese calligraphy as visual elements in these collages. The resulting layers give rich textures to his works. It has been three years since Fong had a solo show in Hong Kong. Whereas his exhibition in 2015, presented by Galerie du Monde, was a retrospective that showcased half a century of his work, “Enlightenment: 1998–2018,” also presented by Galerie du Monde, was more focused, comprising 14 pieces from the last two decades of his practice. In an interview with ArtAsiaPacific ahead of the opening of “Enlightenment,” Fong spoke about his recent compositions, achieving breakthroughs in his art, life in the US, and his thoughts on the future of contemporary Chinese art.

Your artistic style has evolved over the years but what has remained constant is your quest to innovate. Could you speak about that? Have you always sought to achieve “breakthroughs” in your art?

In the early days [of the Fifth Moon Group], this quest to innovate was a result of the circumstances at the time. We were dissatisfied by the stagnancy of traditional ink painting in Taiwan, and wanted to create art that was relevant to the times and reflected a contemporary spirit.

As for myself, I am never satisfied with my own works. This doesn’t mean that I think my work is not good—what I mean is that one’s experiences, point of view and perceptions are constantly evolving. For example, although an artwork I created yesterday may have been good, when I look at it with today’s eyes, I don’t feel the

same way. In terms of breakthroughs, I strive to make small breakthroughs everyday, such as breakthroughs in composition or new developments in technique. Short of innovating, an artist must, at the very least, strive to never repeat oneself.

Are there ever times when you struggle to create something new?

Yes, of course. But this is part of the process in all facets of life. It’s like winning a hand in mahjong, or fishing—when things go smoothly, one might catch a big fish, but at other times, one might be out all day and not catch anything at all. As for painting, I may paint a few hours every day, but the results are always different. There are times when I have been thinking about creating a particular work, and I am able to realize it in just two weeks. On other occasions, I may be working on a particular painting for over two months, but still not be able be complete it.

Could you speak about the fragments of calligraphy that you incorporated into some of the works exhibited in your show “Enlightenment”?

The calligraphies are passages from the Heart Sutra and Diamond Sutra. I chose such texts, rather than poems or song lyrics, because I believe Buddhist texts convey truths about things such as life, death, and our existence, as well as principles to live by, such as “li ku de le” [abandon suffering and obtain happiness].

That said, the calligraphy is part of the composition and serves as a visual element in my work. To put it simply, the viewer doesn’t need to be able to recognize or understand the characters. The calligraphic strokes are an art form in themselves.

In one of the works on display, 2017.10.6 (2017), you inscribed a poem composed by the 17th-century monk painter Shi Tao. You have only used his poetry once before to compliment your work. Could you tell us why you chose Shi’s poetry for this piece?

Shi Tao was an exceptional artist among his contemporaries. I admire the visual structure of his paintings, as well as his philosophy on art, such as his theory on “wuxing lilun” [a style of no style]. However, there is no particular reason why I chose Shi’s poetry for this piece. Like my other pieces, the text is used as a visual element and completes the composition of the work.

How does Buddhist philosophy influence you?

Following Buddhist teachings has allowed me to reach a higher realm of consciousness in all aspects of my life—mind, body and artistic practice.

You first encountered American abstract art in the articles and magazines that you came across at the US Information Agency in Taipei in 1960. What was it that struck you about the works of the abstract expressionist painters? How has your perception of their works changed over the years?

During that period, artists such as [Franz] Kline, [Jackson] Pollock and [Robert] Motherwell, were, like us in Taiwan, also seeking to create a new artistic language. They were in fact looking at Eastern philosophy, art and calligraphy, for inspiration. Thus, as soon as I saw their works, they resonated with me.

However, after going to the United States and seeing abstract expressionist works in the flesh, I didn’t think they were as good as paintings by Chinese artists! I came to realize that Chinese and Western artists develop their practices very differently. In the West, artists move forward to create new forms of artistic expression, whereas in China, artists draw from the influences around them and develop their style laterally.

Do you have a favorite artist and why?

I really admire the painters of the Dutch Golden Age, in particular [Johannes] Vermeer. I’ve seen many of his works at the Louvre in Paris. I very much appreciate his technical skill, treatment of light and how realistically he depicts his subjects and scenes. Vermeer painted assiduously throughout his career, and there is absolutely no pretension in his art. But honestly, I think I admire his work because I am unable to produce paintings like his. If I could, perhaps I wouldn’t feel the same way!

Of course, the master landscape painters of the early Song dynasty are among my favorite artists as well. After that period, Chinese artists have not been able to surpass them and create works with such monumentality and power.

You have said before that you find the textures of tree bark and rocks beautiful. Could you tell us about something you have encountered recently that you would like to recreate in your paintings?

I like to look at decaying, old walls. There aren’t such weathered walls and buildings in California, so whenever I travel, I like to explore and look for them. When I was in India last year, I saw a lot of beautiful crumbling walls. Unfortunately, my trip to Hong Kong this week is so short, I won’t have time to look around. But tomorrow I am going to visit the Nanhua Temple in Guangdong. Maybe I will find some old walls there.

You immigrated to the US in 1975, settling in the Bay Area. Could you share with us a bit about your life in the US?

From the 1960s onwards, quite a few artist friends began to settle abroad. [Fellow Fifth Moon Group member] Hu Chi-Chung went to California, while [painter] Han Hsiang-Ning went to New York; both tried to convince me to settle in their respective cities. Had I been 20 years old at that time, I would have gone to New York, but I was already 42 and had a family—I thus decided to go to California. Also, the West coast is a few hours closer to home than the East coast!

I’m not that interested in the American way of life. I don’t chat with the neighbors, nor do I go out much. At home, I continue to watch CCTV 4 [a channel broadcast in China].

Could you speak about the environment that you work in? Do you have a painting routine? What is a typical day for you?

I’ve moved a couple times over the years within the Bay Area. I used to paint in my garage because I didn’t have a studio. Now I live with my son and daughter-in-law. The house is big and I have my own studio space, which gets lots of light and is very spacious.

I don’t have a special daily routine. I paint, eat and sleep. I do some exercise, although to me, painting is already quite a lot of exercise.

Do you ever look back and reminisce about the beginnings of your artistic career, as well as when you joined the Fifth Moon Group in 1961?

For my generation, we grew up during the war and had to endure much instability, upheaval and hunger. Just to be able to stay alive was a challenge. I feel very fortunate to have survived. All things considered, my journey has been smooth. Moreover, I left my hometown for Taiwan early on, so the Cultural Revolution wasn’t something I had to go through.

Throughout my life, I encountered many young people trying to become artists—more so than musicians and writers. But many gave up. I stuck with art and persevered. I have never thought about doing anything else.

As for the Fifth Moon Group, our activities began simply as an opportunity to hold exhibitions and make friends. Who knew at the time what the future held for us?

How do you think contemporary Chinese art will develop in the future?

I believe China is experiencing a renaissance in all aspects of life—from economics to government policies and traditional culture. The country has developed so quickly. Although I don’t have a comprehensive view, I think the artists most representative of China have yet to emerge. While the Fifth Moon Group played a role during one stage of the development of Chinese art, I believe contemporary art in China will continue to grow. I don’t think it has reached its peak yet.

This interview was originally conducted in Mandarin, and has been edited for clarity and length.

Fong Chung-Ray’s “Enlightenment: 1998–2018” is on view at Galerie du Monde, Hong Kong, until November 24, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.