R

E

V N

E

X

T

Given that Koki Tanaka rejects the idea of traveling exhibitions that are not adaptive or “site-specific,” Precarious Practice is the closest we will get to an unchanging, itinerant show of his works. Published by Deutsche Bank after his selection as their 2015 “Artist of the Year,” the book catalogues Tanaka’s varied oeuvre, successfully conveying his dynamism in a way that also demystifies the Los Angeles-based Japanese artist’s complex—and often nebulous—motives. The feat is all the more impressive when one considers Tanaka’s resistance to motionless representation—his work is mainly comprised of video installation and collective action, usually in non-traditional, or open-air locations.

Scholar Britta Färber’s introduction recounts her participation in Tanaka’s work from his ongoing “Precarious Task” series (2012– ), namely Precarious Tasks #10: Go to a bar located over 20 km from a museum to drink, discuss and watch a film about nuclear power problem (2014). Färber traces her evolution of involvement from participant to co-producer to viewer over less than 24 hours in Eindhoven, Holland. In doing so, she emphasizes the role that trauma plays in Tanaka’s work: though it is not immediately distressing, she points out, it “recalls distressing occurrences that fundamentally call society and our role in it into question.” This particular artist talk-as-social action engages with nuclear history from around the world, particularly Japan’s 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. The distance from Tanaka’s exhibition at Van Abbemuseum to Café de Zwaan, where the film screening took place, correlates to the 20-kilometer radius of the exclusion zone surrounding the infamous power plant in Japan. The chosen café also held significance to the nuclear focus of the evening and Tanaka’s exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum given that it opened its doors in 1973, the same year that Holland’s second nuclear power plant began operating. Participants of Tanaka’s work were invited to watch and discuss a film addressing Finland’s nuclear energy issues. Photos of the evening featured in Tanaka’s museum exhibition the following day. The event was exemplary of how each layer of his work—participants, location, materials, timing—holds weight.

After Färber points to the political gravity of Tanaka’s artistic choices, critic and curator Hou Hanru helps to reveal the concurrent humor in the artist’s work. Hou refers to Tanaka’s exploration of our relationship with quotidian objects and routines and credits the artist for producing “magically intriguing, and even provocative” results. Hou recalls Beer (2004), in which Tanaka documents in a video the pouring of a bottle of beer into a too-small glass and other works in which the audience is privy to his spontaneous bending, stretching and smashing of commonplace objects. The result defamiliarizes these objects and reshapes the automatism of audience perception. More seriously, the curator reflects on the kind of Japan that Tanaka has arisen from: a country and generation haunted by nuclear apocalyptic memories, constantly under threat of natural disaster and troubled by recent economic disappointment.

Curator of modern and contemporary Asian art Doryun Chong closes the first chapter by deepening our understanding of the nation’s political and creative background. He names Tanaka’s postwar avant-garde predecessors and underscores the artist’s integral role in the “politics of resistance” necessary to stave off the rising tide of Japanese nationalism, which threatens to quell “socially engaged art” in the nation.

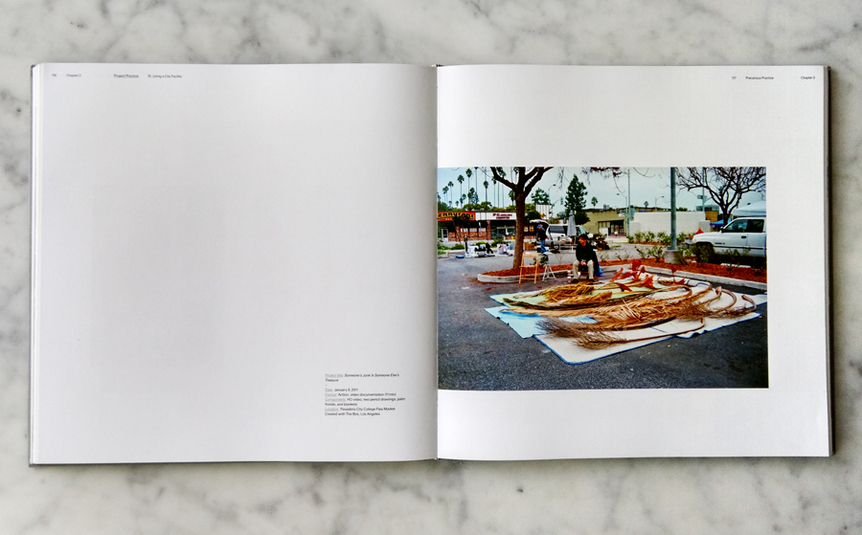

These three scholars illuminate Tanaka’s practice in preparation for “Project/Practice,” the second and central chapter of the book. Tanaka, himself, begins by expressing the preemptive failure to retrospectively explain his work given that the present persistently leaks into our view of the past: “There is no past here. There is only a reconstructed, edited past. In this book, the past exists entirely as a projection of the present,” he says. Nonetheless, Tanaka’s “failed” self-review accompanied by a multitude of images—arranged in an appropriately austere, though elegant, manner—enables access to the juxtaposing humor, sensitivity and political gravity in each of his outwardly haphazard works. His denial of truly objective historical accounts and the reality of how we remember are appropriately conveyed with the chapters and the images’ nonlinear arrangement. Tanaka makes sense of his artistic history by describing certain ideas central to his practice such as “Walking as Remembering,” “Documenting Chance” and “Speaking Abstractly,” which are then accompanied by installation views, video stills or photographs of the relevant works. Tanaka endeavors to reformulate the preconceived: his works look to reconsider, stretch, distort and retort the value of things, functionality of spaces, collective experience, everyday routine, remembrance and artist-audience relationships. He reflects on the blank exhibition space in which visitors were invited to participate in social action, the occasions he sold “used” palm fronds at a Los Angeles vintage flea market, hawked fried rice and art books from a stall in Guangzhou, to the time he asked nine hairdressers to cut one person’s hair simultaneously at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013.

In the final turning of the pages, there is still some mystery in the way that Tanaka has balanced the absurd and the serious over the years. However, after the scholarly and self-reflective light shed on Tanaka’s work, readers may feel compelled to reconsider the simple act of flipping the pages of Precarious Practice and, perhaps, be inspired to enact it a little differently.