R

E

V N

E

X

T

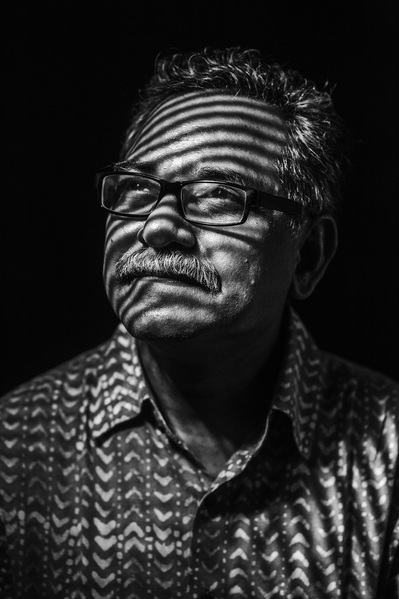

On August 5, 2018, Dhaka-based photographer, educator and activist Shahidul Alam was arrested for publicly speaking against the Bangladeshi government’s crackdown on student-led protests advocating for road safety. In the photographs of him being dragged away by police, emerging from a car on his way to court, and eventually walking out of jail after being granted bail, he is depicted with his fist thrust in the air. Alam’s arrest caused global uproar and the launch of the #FreeShahidul campaign, which circulated flyers and banners bearing an image of the photographer in the same defiant pose. The portrait of Alam—fist raised, a #FreeShahidul wristband on his arm—taken for Time Magazine’s “Person of the Year 2018” issue dedicated to the “Guardians” of truth, cemented Alam’s status as a venerated symbol of the struggle for accountability and democratic values.

In his over-three-decade-long career as a photojournalist, Alam has sought to expose social injustice in Bangladesh, while also founding multiple influential organizations that effectively form the bedrock of the country’s photography scene, including the multifaceted

Drik platform: a gallery, media agency, and Bangladesh’s first Internet service provider; the photography-focused Pathshala

South Asian Media Institute; and the biennial Chobi Mela festival. ArtAsiaPacific caught up with Alam to discuss the 2019 Chobi Mela, the changes in the “Majority World”—a term he came up with to replace “third world”—over the past two decades, his approach to photography, the impact of his imprisonment on his practice, and his upcoming retrospective at New York’s Rubin Museum of Art.

How did Chobi Mela first come about?

I had taken two young photographers to the photo festival Rencontres d’Arles, where I was exhibiting. The transformation that the festival sparked in these photographers convinced me that I needed to do the same for others. Bringing a festival to Dhaka made photography available to many more people here, but it also introduced the work of local and regional photographers to the rest of the world. The community that has been created around the festival was a surprise and a bonus.

What changes have you witnessed in the photography landscape of Dhaka and South Asia in the two decades since Chobi Mela’s establishment?

There are now some very fine photographers in the fray. The quality of the photography and the range of photographic practices among the general public has expanded enormously. There are many virtual groups who only meet when they have an exhibition at [Drik Gallery], but they have thousands of members and consistently produce work of a standard we were simply not used to seeing.

Has the relationship between the Majority World and the West changed in the past two decades? If so, what role has photography played in that?

There are some changes in the relationship, but I believe they stem from the greater economic muscle of Majority World countries, rather than a fundamental shift in attitude. Budgets for photography have been drastically curtailed so the good old days for white, Western photographers who parachuted across the globe in search of stories have largely gone. The Internet has also made a difference. On-ground photographers now supply much of the imagery for stories featured in Western publications, but key decisions are still made at picture desks in Europe and North America. Some Majority World photographers have been able to exert greater authorship of their work, and the quality of the work coming from the Majority World is an undeniable fact, but the power dynamic remains. A key difference has come from the greater use of multimedia, where local voices are more prominent, but even in this case, raw footage is produced in the Majority World, then it gets handed over and the local reporter doesn’t have much say about what comes on screen.

The statement on the theme of this year’s Chobi Mela festival, “Place,” is a poem you wrote. What was the inspiration for this? How have the artists responded to the theme?

We needed a theme that was relevant to the times but created enough room for a diverse set of visual and conceptual practices. The state of the world today required our festival to put a stamp of our current concerns onto our visual production. This was done not only through the artwork and curation, but also through the panel discussions and talks. We kicked off with a discussion called “Freedom of Thought and Expression” because autocrats across the globe are trying to put a lid on dissent. The rise of xenophobia and Islamophobia, coupled with religious extremism, are also things that need to be tackled. We made a strong statement on creating safe spaces and saying no to harassment before the festival even began. We wanted to make sure it wouldn’t be business as usual or a lopsided and largely patriarchal environment, which practitioners find themselves in at many festivals. The artists and audience responded by challenging the old guards and raising questions that were previously under the rug.

What ties your numerous endeavors together?

The underlying theme for all these initiatives is the fight for social justice. We use photography because of the power of the medium, and our strategy has been to work on three areas of intervention—media (Drik), education (Pathshala), and culture (Chobi Mela)—to exert pressure on the political space so those who govern our land are held accountable. Ultimately, we need to produce quality work, and while the politics of our struggles are an important part of the glue, it is the high level of professionalism that makes us a cohesive unit.

What drew you to photography and why do you continue to work with the medium?

Children have played a great role in my life. It was five-year-old Corrina in a small town called Newry in Northern Ireland who made me realize the power of developmental agencies and Western media in the representation of Majority World peoples. A blind boy in Gafargaon reminded me of people’s perception of photography, and Moli, a ten-year-old in Rupnagar, Dhaka, showed me how photography empowered people. We live in an image-saturated world and our minds continue to be shaped by images. Politicians, advertisers and tricksters continue to use photography to their ends. My need to work with photography is not merely to counter that oppressive weight, but also to create a reading of their methods so they are recognized and challenged by ordinary people.

In your monograph My Journey as a Witness (2011), you wrote: “Photographs in particular take on the dual responsibility of being bearers of evidence and conveyors of feelings.” How do you navigate these two tasks when creating your work?

I try to produce work where the politics of the story are embedded in the artwork itself, such as the mode of production in “Kalpana’s Warrior” (2015) [portraits memorializing the disappearance of Indigenous rights advocate Kalpana Chakma, laser-etched on straw mats that reference the conditions of Chakma’s home] and the mode of engagement in “Embracing the Others” (2017) [photos of Bait Ur Rouf mosque, shown on site]. I try to ensure that the two cannot be stripped apart and that my work cannot be used out of context easily.

You were released on bail in November 2018—how has that ordeal impacted you and your work?

My period in jail has given me insights into an aspect of Bangladeshi life that I only knew at a theoretical level before. Not only do I now know how it works, I have a network among former fellow inmates that opens up a whole new space of engagement. I have begun producing work in collaboration with some of them and expect my upcoming work to draw on that experience.

You will have a retrospective at New York’s Rubin Museum in November—what can we expect? What does the show mean to you?

It will be a retrospective, but I will also produce new work, particularly work linked to my period in jail. I have spent most of my professional life building institutions and creating platforms. This show gives me an opportunity to dig into my own work and is an important opportunity for me. I also have a book offer, and while there is very little time, I hope to produce new work, some of which will be not only collaborative, but less reliant on photography.

Looking back on your major series—for example, “Crossfire” (date unconfirmed), “Brahmaputra Diary” (1997–2001), “Struggle for Democracy” (1987–91)—have the significances of these images changed? Where will you be heading from here?

Different bodies of work had different influences. “Struggle for Democracy” was initially produced during the reign of an autocratic military general. Galleries and sponsors dropped our show, and our struggle then was merely to show the work. “Crossfire” [a group of images about extrajudicial killings in Bangladesh] was produced at a time when protests were being voiced, but weren’t making a difference. New forms of intervention were needed. While the show was closed down, it did generate huge response and at the initial stages there was a dramatic drop in the number of “crossfire” deaths. However, a new phenomenon of “disappearances” began and we had to find other ways to respond. “Embracing the Others” is more about opening up spaces for intervention. The work itself is neither novel nor controversial. My work responds to the political climate I operate in, and I shall continue to search for appropriate ways of interaction. I’ll sing, dance, write poetry or take photographs. Whatever works.

Chloe Chu is ArtAsiaPacific’s associate editor.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.