R

E

V N

E

X

T

Carlos Celdran’s career in art began when he joined Business Day as a political cartoonist in 1986, aged 14. Five years later, after a brief stint at the Fine Arts Department of the University of the Philippines Diliman, he transferred to the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in the United States, where he began to explore performance art, interning with the comedic troupe Blue Man Group and the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. As an activist and artist, Celdran believes his mission is to change people’s perceptions. Whether it is how Filipinos see themselves, what a biennial should be, or what art is capable of, he is not afraid to test how people will react to controversial ideas.

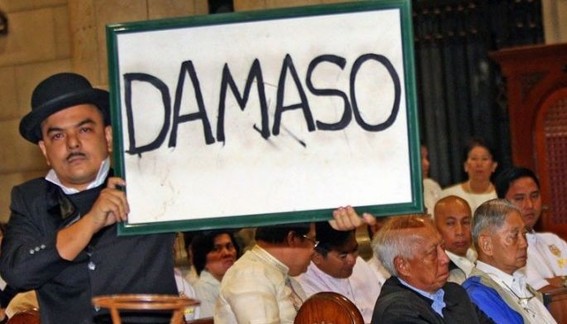

This attitude has landed him in hot water recently. To protest the involvement of the Catholic Church in Philippine state affairs, specifically its vocal opposition to the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Bill, Celdran disrupted an assembly at the Manila Cathedral in Intramuros on September 30, 2010. He carried a sign that read “Damaso,” a reference to the villainous friar in José Rizal’s anticlerical novel Noli Me Tángere (1887), and shouted that Church officials “need to hear what the Filipinos are saying: that 90 percent of the people want the RH [Reproductive Health Bill].” Celdran was charged with “offending religious feelings,” which carries a maximum prison sentence of one year, one month and 11 days. The bill was passed in 2012. Celdran was convicted in January 2013, and has been appealing his case since. With the prosecution rapidly pushing toward his sentencing, he relocated to Madrid in February. AAP caught up with him in Hong Kong, where he stopped by just before his self-imposed exile, to discuss what the move would mean for the Manila native, whose entire practice has been anchored by his birth country.

What brings you to Hong Kong?

On August 1, 2018, the Supreme Court of the Philippines upheld the Metropolitan Trial Court of Manila’s ruling that I am guilty of “offending religious feelings” with my performance Damaso (2010). My lawyer filed an appeal against the ruling in August. In November, the Supreme Court upheld their decision again. Four months—that’s quick for the Philippines. I mean, Imelda Marcos [Philippine First Lady from 1965 to ’86] still hasn’t been imprisoned [for corruption]. There’s only ephemeral evidence against me. She has 1,500 pairs of evidence. I’m in Hong Kong because my lawyer received notification of the Supreme Court’s most recent decision just 24 hours before the deadline for us to submit another petition. If he wasn’t able to file the appeal on time, who knows how quickly a warrant for my arrest would have come. A friend of mine, who is a travel agent, booked me on the first flight out of Manila to Hong Kong. The idea was that I could wait it out until January 7 [the deadline]. January 6 rolled around and my lawyer called and said we were able to submit the appeal on time. He doesn’t think that the Supreme Court justices and their clerks will be able to come up with another upholding within the next ten days, so it’ll be safe for me to go back to the Philippines and say goodbye to my family properly before leaving to Madrid. I’m still a little frazzled. I’m being held together by cannabis oil and a lot of espressos.

Why are you relocating to Madrid?

Luckily my grandfather is Spanish, so I was able to attain a visa to Spain. It’s art in exile now for me, which is a shame because I’m one of the few people who actually likes living in Manila. Several factors made leaving necessary. The speed of the court’s decision was alarming. There’s also the volatility of the Philippine justice system. This new Supreme Court justice [Ramon Paul Hernando] is pretty much the president [Rodrigo Duterte]’s lackey. I’m a known critic of the president, and was a target during his last election campaign in 2016. The last point of consideration was what would happen to me if I did end up in the prison system. Clearly, freedom of speech is under attack in the Philippines.

You said that you never thought you’d be a part of the diaspora—how are you feeling about the situation now?

The Philippines is a postcolonial culture. So many Filipinos don’t want to be Filipino. I’ve always taken the opposite stance in my art. Manila is my petri dish, and I’m really sad to leave it. It’s like an artist being kicked out of their studio.

Luckily, there’s a historical connection between Spain and the Philippines. Now is the time for me to really integrate with Philippine national hero José Rizal, who also lived in exile in Spain. Rizal has been my spirit animal my entire career. He’s my alter ego in my performances—the Sasha Fierce to my Beyoncé.

I saw your photo with the Rizal commemorative plaque in Central, Hong Kong, which marks the house that Rizal stayed in while he was also seeking refuge here. Your performance Damaso is named after a fictional friar from Rizal’s novel. Why is the writer so significant to you?

I helped make that commemorative plaque in Central together with Lakbay Dangal, a Filipino group in Hong Kong that teaches locals about Rizal’s life as a way to lift our national profile.

Rizal was important to me even before this whole thing happened. Unlike a lot of state-sanctioned templates for the perfect citizen, which is what a national hero represents, he was international and outward-looking. The Filipino diaspora—your maid, that service person in Dubai, that deck hand on a ship—are embodiments of Rizal, because these are the people gathering ideas from all around the globe to help improve the country.

Many of your projects are connected to Manila. How has your relationship with the city changed over your lifetime?

I bought the American dream for a few years. After graduating from RISD in the 1990s, I worked in Soho. It was a perfect New York moment that I messed up. I didn’t get the right visa, hung out with the wrong people—many different factors tumbled into one. Then I figured if I was making art about Manila in New York, I might as well do it in Manila, so I moved back in 2002. It worked for me.

I tried different things. At one point, I thought, let’s try going into a church to see if performance art can actually change something on a political level. And, yes! Using the figure of Damaso, 80 million Filipinos who spoke different languages and held different political beliefs knew exactly what I was talking about. They were able to maintain their attention long enough, in a country that doesn’t hold its attention very well, to push through the birth control bill. That was with art. If I went there as Carlos Celdran, it wouldn’t have worked. And that’s why I can say art is transformative.

What fascinates you about Manila’s walled city, Intramuros?

Intramuros was the landing port of all international culture, economy, produce, religion and genetics. If anything went to the greater island, it first passed through Intramuros. Unfortunately, Intramuros was destroyed in the Second World War by the US. Everything that was of cultural significance—the church with 400 years of history, paintings, writings, fonts, the curve of the staircase, the shade of pink on the ceiling—was blown up within hours on February 24, 1945, when the Japanese refused to surrender to the US army. This damaged the Philippines’ psyche. I mean, how can you blame your colonial master for destroying your culture? Then, when everything was razed, the US said, “okay we’ll give you Jeepneys [disused military jeeps].” We’ve been living in a post-apocalyptic culture since 1945. And I think that’s part of the reason why we haven’t come to terms with our own identity.

You initiated the Manila Biennale, which you staged in Intramuros. What was your experience putting it together?

I felt so alive. We were breaking barriers and pissing people off. One thing we forgot to do while putting together the biennale was to ask for permission. Apparently, if you use something as heavy as the word “biennale,” you need common consensus. There was a lot of resistance in the Philippines and some pointless boycotts. We didn’t use tax money; we’re self-funded. We put together an entire biennale for—and I’m proud to say it—PHP 10 million (USD 191,000), through crowdsourcing and ticket sales. We actually even paid taxes for the event. Who throws a biennale for less than USD 200,000?! That’s the cost of a single painting. We did it because we wanted change.

Biennales should be redefined in this day and age. I don’t want biennales to go the way of the Olympics. Countries should not break their budgets for a single event—then you’re just trying to put on the emperor’s clothes. You’re social climbing. What we did is the reverse of social climbing. We did not host the Manila Biennale in a Makati space [where many commercial galleries are located]. We presented conceptual art. We had no art superstars. We did everything—from conceptualization to the opening—in nine months. Until the very day we were meant to open, people thought we weren’t going to do it. And then when we opened the show it was a statement: look what Filipinos can do with our imagination, our context, our history. That’s all we had at Intramuros to create a powerful statement about war.

We increased the number of people visiting Intramuros by 105 percent. They weren’t art people; I’m really proud of that. The locals called the Manila Biennale the “bayan-ale.” “Bayan” means community and home, so in their mind, “bayan-ale” meant town fiesta, which I think is a better way to translate and understand a biennale. I’m interested in bringing art down to the streets.

Is that why you also do walking tours in Intramuros?

Yes, it’s performance art. It’s when you use your body to create something out of nothing.

You recently participated in an exhibition called “The Breathing of Maps” at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media in Japan. You turned one of your walking tours into a video installation. Could you tell me about this translation process?

The show was curated by Mark Teh and was about bringing maps to life. It was a challenge for me because I really had to look at the script of my tour, the story, and my body. Talking about the Manila Cathedral is very difficult without the Manila Cathedral behind you. I’m trying to use Manila’s story in different ways now that I can’t be in Manila any more.

You’re currently making an assemblage work, Guadeloupe de Manila (2019). You’ve worked with assemblage and collage quite frequently in the past. Why is that?

It’s the aesthetics of Manila. Also, art is not necessarily determined by a medium or style. It is determined by how well you can put things together, because art is all about problem-solving. That’s why I use collage—it involves gathering things and putting them together.

What is your plan for the immediate future?

Moving at this time could be good for me because I experienced a lot of difficulty with the Manila Biennale, and because of the court cases, and my political beliefs against Voldemort [Duterte]. Maybe it’ll be good to start from scratch. If there is an opportunity to come back to the Philippines, I would probably take it. For now, the plan is to be in Madrid for a minimum of two to three years. That means the next Manila Biennale is definitely in question. We’ll probably be the Manila Triennale or the Manila Occasionale. But we will do it again. The art world needs an enema. Not because it’s shit, but because it’s stuck. I don’t want it to get stuck.

Chloe Chu is the associate editor of ArtAsiaPacific.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.